-

This overlapping brings doubts about the convenience of the project.

The construction project of a railway that connects the coasts of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, agreed upon by the governments of China, Brazil and Peru, does not have an official route yet. However, through Access to Information requests, we were able to gather information on the proposals of routs being discussed in the Viability Basic Study and on the technical opinion of the Environment and Culture sectors about the possible environmental and social impacts of each option.

After the signing of two memorandums of understanding in 2014 and 2015, the subgroup of technical experts of the three countries, under the leadership of China and the Ministry of Transport and Communications -Peru’s focal point-, is preparing the basic studies for the project. GREFI was able to access the preliminary version of the study. This was elaborated in October 2015 by the Chinese company China Railway Eryuan Engineering Group, which is also describing and assessing the five proposed routes to the ports in the Peruvian coast.

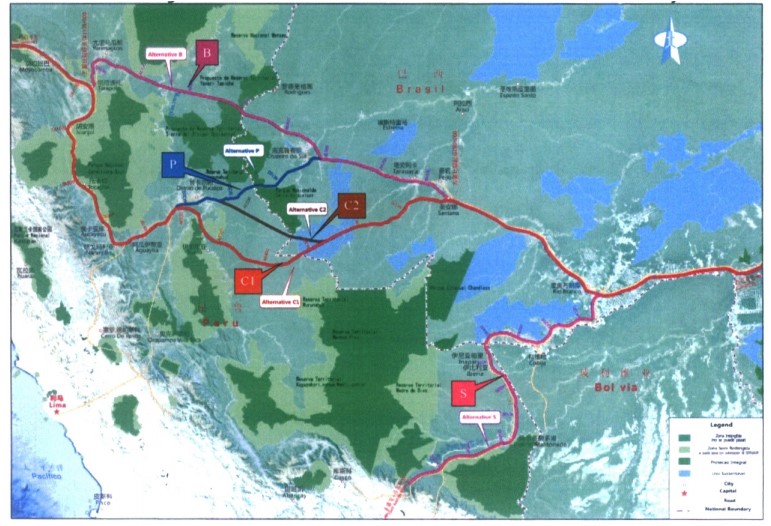

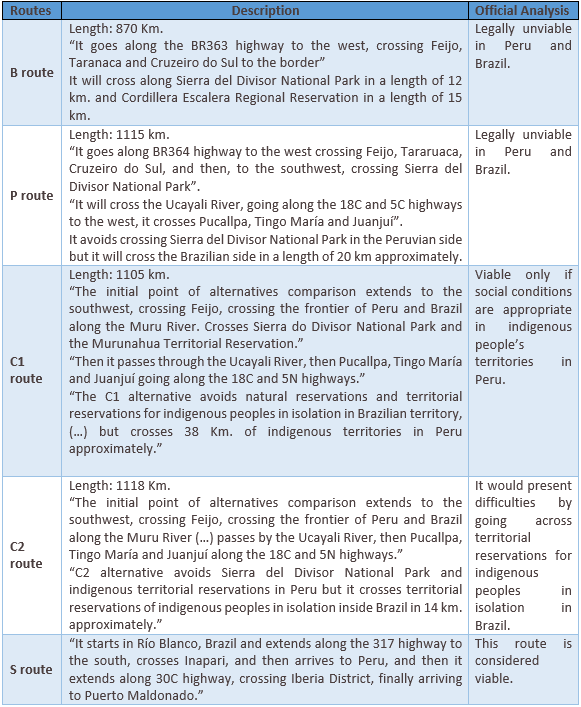

The alternatives are distributed into two main corridors, the Northern – Central corridor and South corridor. Within the first, the routes «B», «P», «C1» and «C2» propose crossing the border through Loreto and Ucayali regions in Peru. As is detailed in the study, none of these options could avoid passing through and compromise natural protected areas or indigenous territorial reserves in Peru and Brazil. However, the study consider and recommends the «C1» route as the most viable alternative.

The «B» and «P» routes goes across the Sierra del Divisor National Park in the Brazilian and Peruvian side respectively, which were considered infeasible in the study by the technical teams. Alternative «C1» and «C2» bypass this protected area to the south; however, in the first case the route passes over indigenous territories in Peru and through reservations of indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation in Brazil, noticing in both cases the existence of social difficulties for the implementation of the project.

In the South Corridor, the «S» route starts at Río Blanco in Brazil and ends in Puerto Maldonado in Peru, following the path of the South Interoceanic Highway. This route would not affect nature reservations or indigenous lands.

Technical opinion of Environment al Culture Ministries

The technical opinions summited in October 2015 by Environment and Culture to the General Directorate of Roads and Railways (DGCF) of the Communications and Transport Ministry -the office in charge of coordinating the Experts Group of Peru-, both agreed that B route should be discarded.

The Viceministry of Environmental Management (VGA) and the National Service of Natural Protected Areas (SERNAMP) discarded this option because it will cross the Sierra del Divisor National Park and the Regional Conservation Area Cordillera Escalera in Ucayali (Oficio N° 313-2015-VMGA/MINAM). The Ministry of Culture, through its General Directorate of Indigenous Peoples (DGPI) also considered (Oficio N°258-2015-DGPI/VMI/MC) that B route will cross the Territorial Reservation Yavari-Tapiche, wich could affect the rights of indigenous peoples in isolation and initial contact.

Regarding the rest of the options, Environment and Culture had different arguments. The VGA and the DGPI determined that P option was viable because it will not compromise protected areas in Peru. On the other hand SERNANP considered that this route will not be viable because it crosses the Sierra de Divisor Park in the Brazilian side.

The VGA and SERNANP considered C1 and C2 routes as viable. Nevertheless both declared that in their way to the north C1 and C2 should be modified in order to avoid affecting the Altomayo Protection Forest in San Martin region. The evaluation of the DGPI concurred in this point, but also observed that C1 crosses indigenous territories and a number of previous consultancy processes should be conducted.

Opinion

César Gamboa, Executive Director of Derecho, Ambiente y Recursos Naturales

There are concerns in form and substance that should be solved before going forward with the Bioceanic Railway project. The first one regarding the transparency of the political process that has been promoting this initiative. The idea of having a connection between Peru and Brazil can be tracked back at least 50 years, but the authorities of the three countries involved haven´t been clear about the interests that motivate the prioritization of this project above other transportation alternatives; especially considering there is already a connection not being used at its fullest, the Southern Interoceanic Highway. There are also other initiatives already advanced and less risky for the environment, like the railway projects that cross Bolivia or Chile in their way to the Pacific.

This observation leads us to the main underlying problem. Although the Ministries of Environment and Culture have analyzed the possible impacts, nothing is known about any assessment regarding the economic benefits of the railroad, nothing about how this project is complementary to other infrastructure initiatives or how does it fit into the national planning. Since the signing of the Second Understanding Memorandum between Peru, Brasil and China, in May 2015, we have asked for information and interviews with the government officials from the General Directorate of Roads and Railroads of the Transportation Ministry to know more about the possible effects on productivity, territorial pressure and on the local producer’s commercial dynamic. Until know, the Directorate has refused to share this information.

If there are no technical studies, which were the economic and geopolitical variables considered? If all of these factors have been taken into account in the feasibility study of the train, why not showing it?

The recently elected President Pedro Pablo Kuczynsky considered the construction of a connection between Pucallpa and Cruzeiro do Sul as one of the 17 projects prioritized in his Government Plan, what may give new political impetus to the Bioceanic Train. From the civil society, we considered that is necessary to learn from the mistakes made in the Southern Bioceanic Highway, in which previous assessments bouts its effect on the expansion of illegal mining were not taken into account. Is in the hands of the new administration to evaluate the economic and social viability of the railroad, stablish proper guidelines as a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) that allows to foresee its direct and synergetic impacts, and finally involve different sectors of the state during its implementation.